Philosophical Differences

When pressed for a reason why it’s worth bothering to vote, you’d find it hard to do better than the response and aftermath of the emerging COVID crisis. If there was ever a cure to the mass apathy and voter lethargy brought on by successive elections then it could be easily found in contrasting responses to the 2020 pandemic.

“They’re all as bad as each other” and “it doesn’t matter which one you vote for” are sentiments being proven false around the world. Almost every country has a unique problem-solving approach to virus containment, mass downtime, and the sudden loss of productivity. Each has been defined by the character and temperament of elected officials in the lead up to the crisis. Each will have its own pitfalls and victories at the far end of the pandemic.

Even now, with ample hindsight and first-hand experience, government officials on the extreme edges of the political spectrum seem to be in a strange sort of denial about a current and ongoing threat. At the same time, comparably sized nations on the other end have implemented Universal Basic Income (UBI), effective distancing, and emergency measures.

Each approach, from one extreme to the other, is a governing choice dictated by the rhetoric blasted at the electorate before taking office. The current pandemic is an unprecedented event in our lifetimes, but anti-science, populism, and consequences be damned ideology is anything but new.

Tone Matters

When leader’s tell you they are more interested in ideology and rhetoric over science and logic, it’s a good idea to listen. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson ran successive campaigns—from Vote Leave in 2016 to the general election in 2019—ignoring science, logic, and reason to spectacular effect.

When the numbers said one thing he was never afraid to say the opposite. When scientists, researchers, and experts in their field told one story he was never shy in denouncing the very idea or need for science or expertise at all.

As a solution for the future, it turned out to be a phenomenal, if unethical, strategy. During an ongoing pandemic with real life, life and death consequences it is one which has been found largely wanting.

Had we elected (or had the chance to elect) a scientifically literate government, they may have had more luck recognise a contagious pandemic abroad as a threat within our own borders too. They would have certainly been better equipped to act to the best available science and expertise of the time. Yet, this is not the government we had and Neither of these things came to be during the approach and arrival of COVID-19.

Beginning Of An Era

Both Matt Hancock and Boris Johnson attended talks over the virus as early as January 7th. During which time the outbreak was still an emerging threat in China. If concrete steps or actionable plans were implemented during these talks, they were not readily apparent over the next two months.

The outbreak, predictably, grew exponentially in china and quickly began to shift around the globe. Throughout February, the initial response was surprisingly strong and coherent.

Test and trace practices were implemented at scale to track down every case that entered or appeared within the country. Those who had come into contact with a carrier were treated and isolated in an attempt to contain the spread.

By the 12th of March, when the pandemic had taken hold in Italy and spread throughout Europe, test and trace was abandoned entirely. A new way of working, in opposition to World Health Authority advice and expert guidelines, was implemented almost instantly. Efforts and action on currently open cases were halted in favour of a new plan known only to senior government officials.

Once again the same team in charge were saying no thanks to experts, science, and researchers in favour of political advisors and party officials. A vast divide was beginning to open between countries implementing strict, early testing and isolation measures and those not yet willing to do anything at all.

The UK Prime Minister announced on the same day the “worst public health crisis for a generation” was about to hit the country”. But lockdown was not yet discussed. ‘Advice’ to avoid restaurants, bars, events, and gatherings was handed out but no concrete action was forthcoming yet.

While many countries across Europe took the hard-won lessons from Wuhan and Italy, the UK stubbornly held out. Germany implemented vast and widespread testing, and an early lockdown to halt the virus in its tracks. South Korea underwent no lockdown at all, implementing instead exceptional testing measures which prevented COVID-19 from gaining a foothold in the general population.

Ticking Time

Almost every piece of available evidence suggests that the government at the time were pursuing a light-touch strategy of herd immunity. It’s suggested the Prime Minister’s lead advisor went into the pandemic with the hope of riding out the wave of death and catastrophe before summer comes around.

Despite the evidence for it, it still feels almost too callous, too bold, and too stupid to believe. Seen out to its natural conclusion, estimates suggest anywhere between a quarter to half a million people would have been killed by little other than a complete disaster of decision making.

On the 16th of March the government’s advice strengthened. Perhaps, as has been suggested, when the reality of the situation was considered again.

Throughout mid-march sports fixtures both major and minor were still well attended, gigs went ahead and life remained more or less normal. The Cheltenham horse racing festival alone was attended by over 60,000, the champions league fixture in the same week a further 50,000 again. many attended both from across Europe where the virus was known to have a strong presence

Each of these events are now sites of extraordinary interest to epidemiologists. They share a strange interest in the same way as sites such Chernobyl hold our attention. They are epicentres for viral outbreaks which killed people by spreading the virus far and wide. Delays in these areas done more than simply accelerate the spread of the virus. Inaction and indecision appeared to turbo-charge it to new levels.

It was the 23rd of March before lockdown in the UK was finally announced and introduced. At least 75 days after initially learning of the virus and its impacts. Almost an entire month after decisive public action would have been prudent.

Carbon Copy Response

If the Scottish government had the capacity, desire, or foresight to act differently from the UK government, it was a skill that remained largely unused. Since the beginning of the crisis, the First Minister has offered daily briefings scheduled parallel to those of the UK government. Their purpose, seemingly a reminder of adult leadership if nothing else.

Yet, despite a marked difference in delivery and style, Scotland’s broad response to the outbreak was largely in lock-step with the rest of the UK. No attempt seemed to be made to lockdown earlier or ramp up testing while the UK floundered. Both moves which were called for at the time and widely regarded as necessary to ease the burden which we now have to pay.

Whether our synchronised movements are a result of the same poor advice, being legally bound to the UK wide response, or a sudden desire to follow the lead of the UK government remains to be seen. It would be interesting, if not instructive, to find out why decisions were made precisely how and when they were.

A Departure

Whatever the reason for such a close connection then, seems not to hold for the next phase of the pandemic too. Scottish government officials have finally talked at length on their willingness to depart from the UK plan should it not suit their current advice.

The UK government appear to be in the process of very publicly paving the way for a return to normal and imminent easing of restrictions. As early as Monday restrictions UK wide could be changed. The Scottish government seem at pains to stress these changes will not be mirrored north of the border.

Discussions at the Scottish Government’s daily briefings have shifted to focus on the current science and thinking behind the strategies employed. A seemingly open and frank discussion about the method behind the decision. The public, at least north of the border, appears to be an adult audience once again.

The current phase of the pandemic is one which is uniquely frustrating and difficult to bear. Countries who acted fast, decisively, and according to the science are beginning to resume business again while those who stalled, floundered, and failed are forced to watch-on.

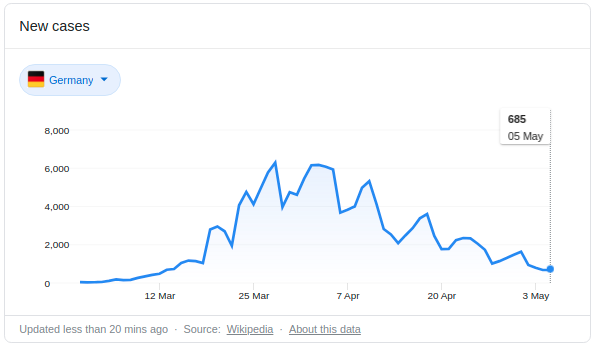

Germany, whose population exceeds our own by 20 million, have reduced their numbers to under 700 cases per day. Even with extensive testing, Germany has seen under 170,000 cases and 7,000 total deaths as the virus winds down past its peak. This compares to 195,000 official cases of our own and 29,500 deaths by government numbers.

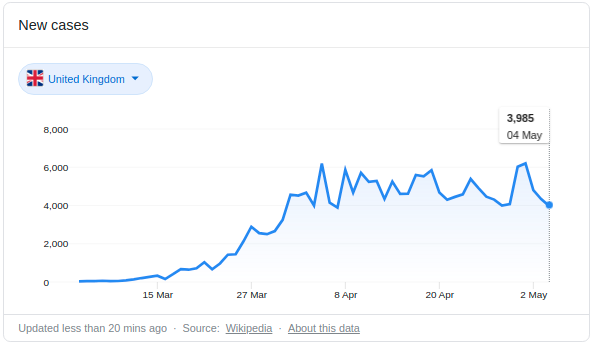

The decision to ease restrictions and return to business requires the number of cases to be low enough that testing, tracing, and isolation can have a meaningful effect on preventing future spread. At 4,000 cases per day, it’s not a marker we’re even particularly close to yet. Those early days wasted turn out to have an enormous cost through later phases.

The Path Forward

Precisely how both governments extract the country from such an unenviable position raises more questions of its own. The Scottish government released a document this week which describes the “test, trace, isolate” approach expected for the weeks and months ahead. Inside, a single paragraph talks about the need for increased and improved integration with the UK government’s much flouted NHS mobile app which, the government have said, will define the countries contact tracing strategy.

That Dominic Cummings and the Vote Leave team are asking for the trust of the nation is as bold a move as any made during the crisis. That it’s even possible people may well trust them one more time is an exercise in collective insanity.

The mobile application itself, a tool for gathering and maintaining tracing data is a spectacularly neat idea. It relies on only local device-to-device communications and maintains its own data locally without any need to continually upload data to the cloud. Whose to bet that such a feature will be activated eventually if not from day one.

Employing big data to solve tricky problems is not a new approach for the current government. The PM’s chief advisor is widely thought of to have played a leading role in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The scandal, one which “shut down” the company, abused the data of social media users for all it’s worth and tested the UK electoral system to near breaking point. That their solution to COVID-19 involves the collection of yet more personal data isn’t a huge surprise.

A Brand Aware Pandemic

The mobile app solution appears to be only the latest of the opportunistic moves made on the back of the crisis. As early as mid-March, ventilator contracts bypassed traditional firms and manufacturers in favour of inexperienced allies in unrelated manufacturing industries

It was a trend which continued throughout the duration of the pandemic. Boots, Deloitte, KPMG, Serco, Sodexo, and Plantir have each been tasked with the purchasing an of personal protective equipment (PPE), NHS data, and the construction of temporary relief hospitals around the country.

The NHS, celebrated by the Prime Minister with a weekly clap at the doorstep of number 10, is being privatised in broad daylight just the other side of the door. The current crop in charge simply asks once more that you trust their judgement at the end of the crisis to reverse the steps they have openly discussed and moved towards since taking power a decade ago.

A Difference In Power

Those in charge at the start of the crisis were asked why it was taking so long to create a financial package that provided for people during a time of global pandemic. The response is perhaps one that defines the current government more than any election broadcast, daily briefing, or party poster.

“We have struggled to find a way to avoid paying people who do not need help.” Government sources said. The current government are explicitly more concerned about overpaying those who don’t need help than underpaying those who do. A similar sentiment is reported to have kept them from entertaining a temporary universal basic income for the duration of the crisis.

The Scottish government, in comparison, is openly discussing the concept of UBI and its implementation in the aftermath of COVID-19. They are reported to be considering the unique case of the pandemic as a strong case for its implementation rather than the defining case against.

While the entrance to the pandemic looked broadly similar on both sides of the border, the exit is looking like it could scarcely be more different. The Prime Minister is looking more and more like the US president in response, style, and substance by the day.

The US government appears to be leading its country into a mire of COVID cases and deaths which will reach into the end of the year. A difference in ideology, science denialist in its largest and most popular form, will cost tens of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars a direct result of an unwillingness to act.

Here today, the jury is still out on the exact cost in lives and money that inaction and a poor entrance to the pandemic has and will cause.

As the UK splits into constituent countries in the way they exit lockdown, it’s increasingly important to note each and every difference in both tone and strategy. Learn precisely what time of government you are voting for and why and that they are certainly not ‘all the same once they get into power’.