Is The UK Election Fit For Purpose

One of the most commonly repeated talking points of British politics is the outsized number of voters who didn’t vote for the winning party, leader, or legislation. In the UK, winning candidates don’t hinge on popularity only uniqueness. First Past The Post (FPTP) has been the way elections have been fought and won over the last 70 years. Simple, straightforward, and easy to understand FPTP stands out as being one of the single worst election methods currently in use worldwide.

We don’t have to look into high-tech solutions or complex mathematics to find better, more representative, ways to ballot the country. There are better methods currently in use nationwide to decide local council seats and MPs for constituent countries of the UK. Every single one delivers a more balanced and more representative of the nation’s voting intent than the one used to elect MPs for the United Kingdom.

Our 70-year marriage to FPTP is testament to little other than how well it works to the advantage of the two primary parties. While most modern parliaments are built on systems that inhibit single or even dual party domination; FPTP instead promotes it.

FPTP Voting

FPTP is the simplest possible ‘winner takes all’ method to ballot the public. Every voter casts one single vote to mark their choice of the preferred candidate. The single candidate with the highest number of votes wins the seat.

On the face of it, FPTP seems fair and a sensible way to count votes. It’s easy to understand, simple to count, and intuitively seems fair and sensible.

Practically implemented, the resulting representation and the balance of parliament is skewed astonishingly easily. No real-world application shows the inherent problems quite as well as the 2015 UK general election.

Suffering greatly from political gaffs and broken promises in the aftermath of the 2010 election the Liberal democrats faced complete obliteration at the ballot box. In the end they were rendered largely irrelevant but could have secured a much worse fate.timon-studler-fI8yIH-rV5I-unsplashSuffering greatly from political gaffs and broken promises in the aftermath of the 2010 election the Liberal democrats faced complete obliteration at the ballot box. In the end they were rendered largely irrelevant but could have secured a much worse fate.

Between the two elections, the party fell from 23% of the popular vote to just under 5%. For their trouble, they won 8 seats in parliament compared to the 62 they held in coalition government during the previous session. It was one of the major political shifts of the year. Another major change of the time was the rise of UKIP from fringe group to major political force.

UKIP rose in ranks to claim almost 13% of the vote, though received just a single MP in exchange. Despite more than one and a half million more votes and more than the Lib Dems, the party was barely represented outside of the Conservative seats.

The 2015 election was particularly notable in how far the make-up of parliamentary seats seemed to lie from voter intent. Most typical elections end with a parliament skewed a modest amount one way or another, 2015 strayed remarkably far. As a method of creating a representative parliament, FPTP is notably inadequate.

Spoiler Effect

The single largest flaw in FPTP comes from a phenomenon known as spoiler effect. Part of tactical voting and a key component of UK elections, spoiler effect comes into play when voters are forced to abandon their preferred choice of party or candidate in favour of someone with a realistic chance against a candidate they truly can’t stomach.

Spoiler effect promotes voting for a lesser of two evils, a candidate that is less representative of voter intent but a better choice than another candidate on the ballot. Through repeated cycles, the result of rising poll numbers and an increasing gulf between candidates and voter is a convergence on two mediocre parties that roughly approximate some of the views of most of their voters.

The rise of a third party, which may hold many of the views on one side of the aisle and none of the other, can only ever disadvantage the party which they are closest aligned to. Third parties parasitically draw almost all their voters from similar parties and nearly none from their opposition—resulting in both like-minded parties spoiling each others election chances.

Alternatives to FPTP

Alternative Vote (AV)

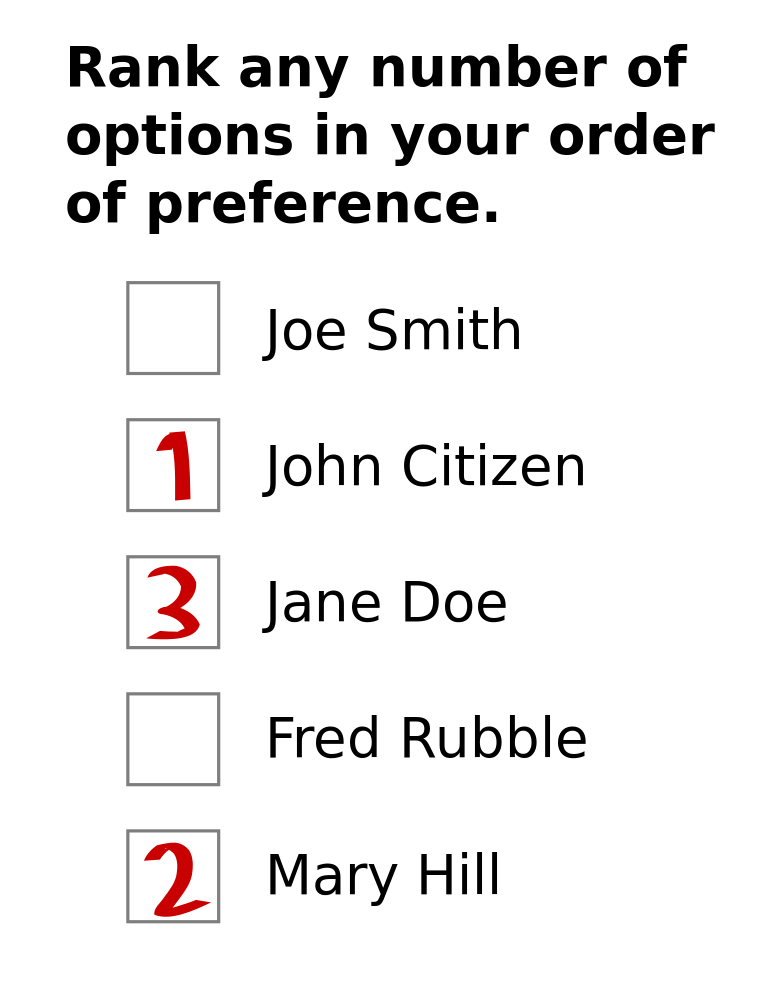

Perhaps the simplest to understand and easiest to implement, a strong upgrade to FPTP is Alternative Vote. Rather than placing a single check mark on their chosen candidate, voter instead rank their preferred choices from best to worst.

Commonly used around the globe, AV has the advantage of requiring very few changes to the current ballot and a remarkably shallow learning curve. Though simple to learn and easy to understand, the system does have its critics. AV was labelled “crazy, obscure, [and] undemocratic” by then Prime Minister David Cameron shortly before putting EU membership and legislation to the popular vote.

Alongside adoption in Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, a number of areas throughout the UK adopt AV for their own elections. A similar ranking system is currently employed in local council and Scottish parliamentary elections without issue. As a concept that the public can understand it’s a relatively simple one.

Using AV, the party with the lowest number of votes in an election turnout is eliminated from the race, their primary voters next choice candidate awarded their single vote instead. The process is repeated until an outright winner can be declared.

The result of the process is electing a candidate that is most agreeable to the largest percentage of voters. The makeup of the resulting parliament is undoubtedly more representative than FPTP. Most notably, it reduces the spoiler effect by allowing voters to choose their truly preferred candidate without worrying about the effect this has on the opposition. There are better, more effective, and fairer systems out there but as an easy fix AV is a notable improvement.

Single Transferable Vote (STV)

Further up the scale, with a little more complexity than AV is Single Transferable Vote. The scheme uses a ranking from best to worst, similar to AV, though counts votes over and above those needed to win for the next choice parties.

Opponents of moving from FPTP often cite this additional complexity as a major sticking point. It’s often claimed that anything other than painfully simple is too complex for the public at large to understand and use. Single Transferable Vote however, is in common use today. Local council elections are decided using STV to ballot the public and have been for some time. Few could contend that local council elections, though under-attended, are difficult to understand.

An STV election elects three representatives from a wider constituency to ensure a broader range of parties are present. The votes required to win are determined by the number of votes cast divided by the number of candidates standing. Votes attributed to a winning candidate who has already crossed the winning line are given to their next choice candidate to ensure ballots are never wasted.

The result is a much more representative body that contains members from every party that has a significant voter presence. STV improves over both AV and FPTP for creating a more representative parliament. Though further departed from our current system and more complex, it’s not a system entirely alien to the UK public.

Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP)

Scottish general elections use Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP) to elect members to the Scottish parliament. This involves voters choosing a favoured party in addition to ranking local candidates. These party votes go towards electing ‘list’ members. who are appointed by the party.

List members are politicians put forward by the party to take a seat in the next session as a result of party votes rather than constituency once. Votes are weighted in a system designed to prevent outright election winners and ensure a balanced and representative parliament at every session.

Some notable criticisms of MMP are that it creates candidates who prioritise party politics over voter interest when faced with being de-selected from the party list. Though more detailed than each of the previous systems, there’s little doubt that it creates a more representative and balanced parliament as a result.

Current System

The major feature of FPTP that no other system can replicate is the outright favour of the two parties dominating the current parliament. FPTP promotes a two-party system, and both leading parties can count on remaining comfortably close to the government bench as long as it’s implemented in the UK.

Modern parliaments are designed in every respect to be forward-thinking. The architecture, systems, and politics are built to prevent single-party domination and a stranglehold on power.

Westminster’s traditions and antiquity have been preserved from the ground up. The opening of each parliament includes a day’s worth of pomp, ceremony, and amateur dramatics by a large contingent of well-paid MPs. This reluctance to progress and change has an unbearable price.

There’s no lack of viable alternatives to the way things are done. Examples here are just a few which vastly outstrip the capabilities of the current system. Like many of the buildings and almost all of the traditions, FPTP is long due some serious renovation.